THE FIRST MUSEUM SHIP? TRACING THE GOLDEN HIND’S LEGACY FROM DEPTFORD TO LONDON BRIDGE

After completing the first English circumnavigation of the globe in 1580, Sir Francis Drake returned to Deptford to a hero’s welcome. Queen Elizabeth I ordered Drake’s ship, the Golden Hind, to be preserved “as a monument to posterity of that famous and worth exploit” (Philip Howard, The Times, 1977). What followed was an early and remarkable instance of public historical interpretation: the ship became a long-standing tourist attraction and may have been, arguably, the world’s first museum ship.

A National Symbol Left to Drift

The Golden Hind was lodged in a specially constructed brick dock at Deptford Royal Dockyard, likely within the area now known as Convoys Wharf (MOLA Post-Excavation Report, 2013). She remained visible to the public for decades. Contemporary Dutch maps and Benjamin Wright’s 1606 chart mark her as “Captain Dracke’s Ship” (National Maritime Museum Maps G.218.8 & G.218.9). Some suggested more grandiose ways to commemorate Drake’s feat - including mounting the ship on the broken spire of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. Instead, the vessel remained moored in Deptford, where she slowly decayed. By 1618, the Venetian ambassador’s secretary described her as resembling “the bleached ribs and bare skull of a dead horse” (Howard, 1977).

Despite her condition, the ship remained an attraction until around the 1650s, when she finally fell to pieces. Three chairs were later made from her timbers, one of which is still held at the Bodleian Library (Deptford Dockyard Heritage Report, MOLA, 2013). A new dock constructed in 1667 may have disturbed what remained of the hull (Banbury, 1971).

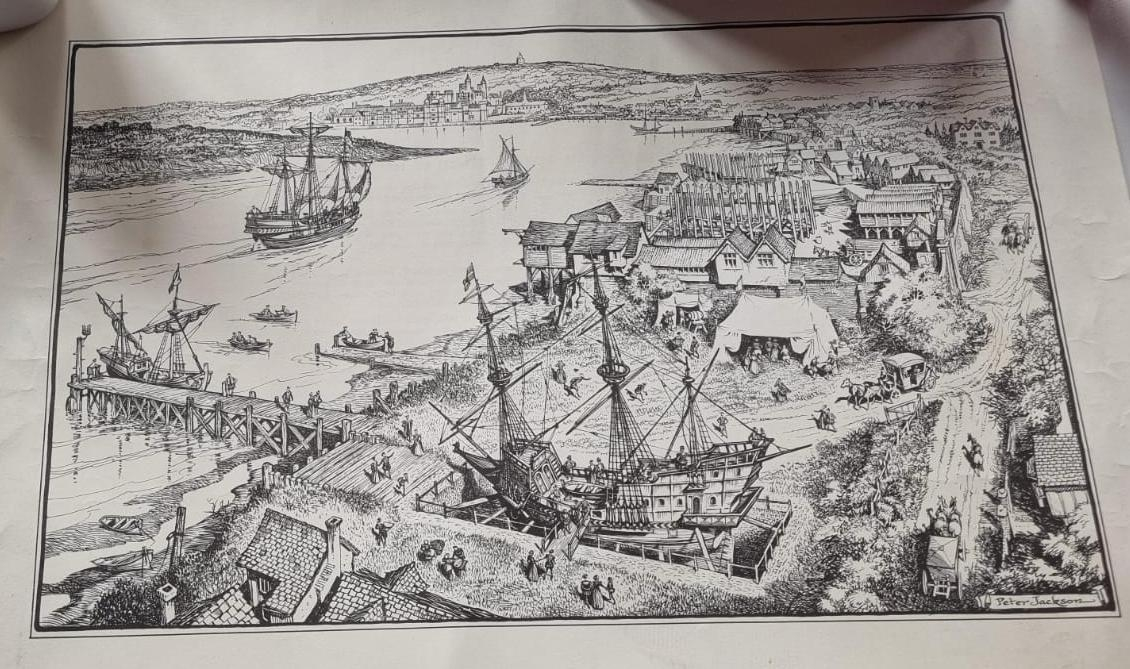

Excavation at Deptford: X Marks The Dock

In 1977, archaeologist Peter Marsden led an excavation at Deptford Wharf. The project, sponsored by the Evening News, aimed to locate traces of the Golden Hind or her custom dock. Public interest was high - some reports implied the ship itself might be uncovered - though Marsden stated that his aim was to understand the context around where the ship had once been displayed. While the excavation revealed evidence of 17th Century shipbuilding (including tar deposits and wood shavings), it did not locate the ship. However, Marsden noted that the ground was significantly waterlogged - a promising sign for preservation. He concluded:

“The lower part of the ship probably survives as waterlogged timbers, and… one day it may be found” (Marsden, personal correspondence, 2024).

A trench parallel to the river, Marsden suggested, might reveal surviving remains - but such an excavation would be extensive and expensive.

The Dockyard That Launched an Empire

Deptford was no stranger to important ships. The Tudor dockyard, established in 1513, was a key centre for naval innovation. It was the site of construction for famous galleons like the Mary Rose and Great Harry, and hosted early East India Company operations from 1600 onward (Secret Gardens, Vol. 2; Loades, 1992).

Against this backdrop, the public exhibition of the Golden Hind in the late 16th and 17th Centuries takes on new meaning - not just as national pride, but as part of a broader culture of public access to naval achievement. As one heritage report put it:

“Drake’s ship was a tourist attraction for some decades, before it fell to pieces in the 1650s” (MOLA, 2013).

The Golden Hinde Today: A Living Legacy

In the 1970s - nearly 400 years after Drake's return - a team of shipbuilders used traditional methods to create The Golden Hinde, a full-scale, sailing reconstruction of the original ship. She launched in 1973 and completed 140,000 nautical miles of sailing before docking in Bankside, London, where she remains today. Still a family-run project, The Golden Hinde continues the work of her namesake: welcoming the public aboard, telling stories of exploration and empire, and engaging new generations with hands-on maritime history.

As we celebrate International Museum Day 2025, we’re reflecting on this dual legacy - one of timbers buried in Deptford mud, the other of sails raised in Southwark skies. Both versions of the Golden Hind(e) have played a role in public history, long before the word "museum" meant what it does today.